There are new solutions for work and learning, but are we, as a society, open to shifting from the familiar to seize these opportunities?

I sat down with Ryan Stowers, Executive Director of the Charles Koch Foundation, to discuss openness in the sector. We lay down a definition for openness, look at shining examples of learning innovation, and consider the risk of holding to the status quo.

Michael Horn:

Welcome to the Future of Education. I'm Michael Horn, and you are joining us at the place where we are dedicated to building a world in which all individuals can build their passions, fulfill their human potential, and live a life of purpose. There are very few people that I know who exemplify that more than the Executive Director of the Charles Koch Foundation, Ryan Stowers. He's a man who's a friend and has offered a lot of wise advice over this journey for individuals of many organizations over the years. So, Ryan, great to see you. Thanks for being here on the Future of Education.

Ryan Stowers:

Thanks for having me, Michael, and thanks for all that you do.

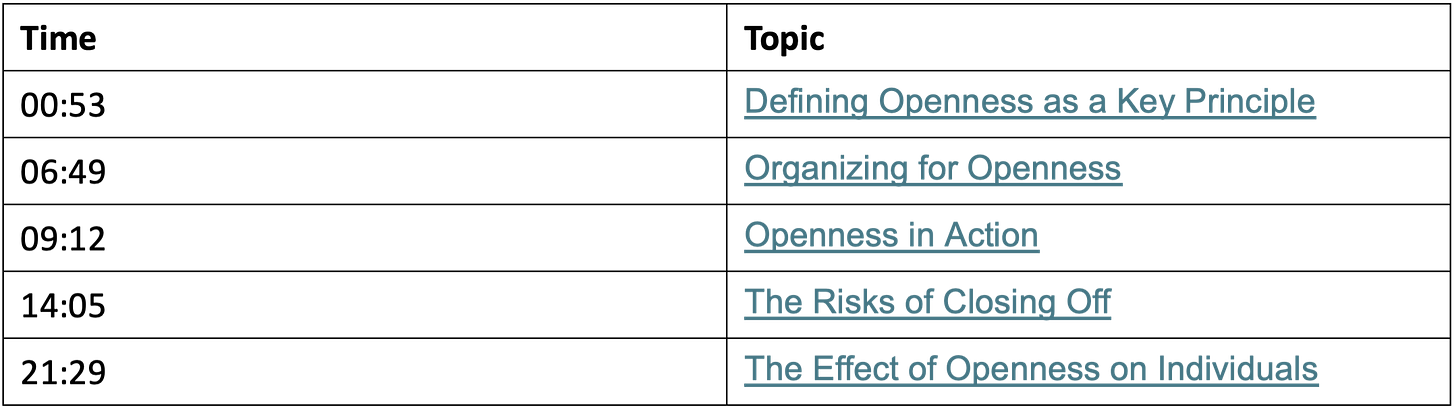

Defining Openness as a Key Principle

Michael Horn:

No, you bet. I've been looking forward to this conversation for a while for many reasons. You all at the foundation have been working with so many entrepreneurs, educators, and employers, helping rethink, how we develop talent in this country so that all individuals can live into those ideals that I espoused up front. You know like purpose, and that businesses will also benefit in the process. So as a result, you get this bird's eye seat on all these cool journeys about how people are doing things differently from the way they've always done it. This will be the first of a series of conversations we'll get to have. I'll set the table because, over the past couple of months, I've gotten to explore a few of these principles with your grantees. The concept of mutual benefit with Scott Pulsifer of Western Governors University. And what I think you would call the broader dimensions of talents with Kathleen St. Louis Caliento of Cara Collective. I'm looking at your book that the Koch Foundation and Charles Koch Industries put out Principle Based Management. You have this other one in there called Openness - key principle. I'd love you to define what openness means to you and why it matters because it's one of those that I think on the surface, the word could mean lots of different things to lots of different people. And so it requires a little explanation.

Ryan Stowers:

Yeah, thanks, Michael. When I think about openness, I think the best way to define it is the free movement of ideas, resources, and people, and that generates knowledge, innovation, and opportunity. We think that's been critical to fueling progress in society, and we think it's going to continue to be important moving forward. So I think that's the best way to define it.

Michael Horn:

No, that's a good definition, and you couch it in that larger narrative of progress. In the context of learning and education and the workforce, what does openness sort of look like?

Ryan Stowers:

Yeah. And you and I have spent a lot of time on this. If you think of a system that right now, from my perspective, needs thoughtful consideration of openness, it's the work and learning ecosystem as we think of it. For so long, the focus has been on things like credit hours, seat time, and degrees, and it's not working. It's helping a select few get to the point where they can reach their potential, find purpose and meaning, and produce value for themselves and others in society. But for the most part, it's leaving millions behind, and it's setting a lot of people up for failure. So in this context, openness means, and you said this, you use the term rethink. Openness would lead us to consider that we haven't figured this out and that we should consider changing the way we think and act about work and learning to bring about better outcomes for all people with a recognition that we know how to do this. We've seen it work in other industries, we've seen it work in other spaces. We should put that kind of openness and innovation and a willingness to rethink or think outside the box to help us find better solutions for people. From our perspective, the answers are there. If we engage in this kind of openness and backing up a bit, you see it work at a societal level. A more open society is going to be one where new ideas are welcomed, where those new ideas are applied, and where progress is made. In the physical world, you see it like closed systems, they inherently stagnate and eventually fail. If you apply that to the world in which we're working, you can see how in the work and learning ecosystem, you've got more than three stakeholders, but I'm thinking of three in particular. The learner, the solution or educator, or the solution provider, and then the employer. Because so much learning occurs through work in our lives, getting all three of those stakeholders to think and act differently about how they engage in the work and learning ecosystem, I think, can bring about incredible results. So it's in that context that openness, I think, applies very much.

Michael Horn:

Yeah, I'm just thinking of so many things as you're talking that through, Ryan, because two of the things that hit me, I think of Glasnost in the Soviet Union, Gorbachev being like, we got to open up. We have to have new ideas. Then I think of the American entrepreneurial system over the last many decades compared to say a place like Japan. Our friend Clay Christensen would always say Japan disrupted the US economy. They played the game once, but then they had no mechanism of venture capital or laying employees off to create new companies that would come create that next wave of growth. As a society, it was relatively closed, whereas, in the US, we have some painful moments, but we keep having entrants come in and rethink and bring new ideas.

Ryan Stowers:

That's right.

This episode is sponsored by

Organizing for Openness

Michael Horn:

So it's an open society that keeps rejuvenating us over time. I guess the question is, so is it the existing organizations rethinking, or is it being open to new organizations maybe coming in and reinventing the DNA of a sector?

Ryan Stowers:

Yeah, I mean, I think it's going to require both. If you think of just the education system. Look at post-secondary ed right now. There are attempts. A lot of these attempts are well intended. I mean, a lot of these people are trying to help others reach their potential. Universities are, I think fundamentally they are. But if you look at the competition that new alternatives face in the post-secondary ed market, for instance, universities are getting $250,000,000,000 in subsidies to run their business. The anti-competitive forces that create an alternative to be relevant and provide a solution that will empower people are extreme. That's an example of where if we don't rethink what we're doing in the student finance and funding question, we could inadvertently create a more closed system than a more open system that would allow innovation. That would allow, to your point, new entities, new individuals, and new entrepreneurs to come into the space and try to make things better. And to have incumbents and people in the traditional space not view that as a threat, but view that as an opportunity to learn and adjust as well. So that's just one example. I think it's got to be a combination of both. The current actors being willing and open to changing the way they think and act, and then new entrepreneurs coming up with new ideas and driving and spurring that kind of innovation with the intent of creating a marketplace that reaches all learners in a highly individualized way to help them reach their potential. I think we can do this.

Openness in Action

Michael Horn:

So let's talk about your portfolio because you guys support so many interesting organizations. It's a compelling point you just made that both/and have to be part of this openness. Who's doing this? Well, who's doing this right, right now, that's really bringing in new ideas into the sector, exhibits that openness.

Ryan Stowers:

So just a couple of groups that are maybe on the side of the traditional approach. These are folks that you and I know well. We talk to a lot of these folks a lot. If you look at what Michael. Crowe's done at ASU, he's been open to considering culture change in a space that's been fairly resistant to that kind of culture change over time. Rethinking the role that the university plays in society in order to help more learners gain access to knowledge and skills they need in order to be successful. More open to bucking the one-size-fits-all kind of standardized approach to one that's more. You know, Michael would say this. I don't think Michael's figured it all out, but he's made some huge strides in doing so. Another one that comes to mind, you've interviewed him, Scott Pulsifer at Western Governors University. The fact that they take a competency-based approach to them, from figuring out where they can meet students and empower them to close the gap. To getting the knowledge and skills they need for in-demand jobs, that competency-based approach is highly innovative relative to where higher ed's been in the past. I think you're seeing the outcomes through the results that Western Governors is producing. Another couple that comes to mind that are maybe smaller and less well known but equally impactful is Reach University where they've gone in, and this is where you can bring the employer in, but they've gone into different sectors directly with groups that need to hire people, and they're not able to find people with the right skills, knowledge or aptitudes to meet the demand. So they started with K-12 teachers going into school districts and saying, hey, if we can identify dormant talent either through teaching assistants or substitute teachers who have… Some of them have 20-30 years of classroom experience, but they don't have any way to take that to the market and say it's worth anything other than giving them another role as an assistant or as a substitute. So Reach is going in and saying, how can we help that substitute teacher close the gap in a low-cost way to get them the credentials they need and then have the district recognize them as a fully trained teacher, able to run a classroom and teach students? And now they're going to nursing and manufacturing jobs. Reach University is a great example of what can happen when we take an approach based on openness and in this space coming up with a highly innovative idea that has the potential to unlock things in ways that otherwise wouldn't happen.

Michael Horn:

I love all three of those examples and for different reasons. I mean, the way Michael at Arizona State redefined excellence away from who you effectively exclude to how you can take anyone regardless of their starting point. How far can you take them? And then, Scott, obviously I'm a big fan of what Western Governors does with competency-based learning and fundamentally changing the measure of learning from time to actually what you've mastered. Then Reach, Mallory's, longtime fan club of what they've created. It's interesting about the last one with Reach that required… and I guess they all do to some degree. It's certainly true for Scott and Western Governors as well. But that's an explicitly big change in terms of the connection with the businesses, the employers in this case. Her’s is school districts, but it could be companies. I guess the question is what's the downside for businesses if they don't embrace openness? Because I'm sure it can feel scary. It's upending the rules of how you have operated. Obviously, there are some great upsides in terms of dynamism and sort of innovating the future. But I can imagine a lot of the colleges or employers that maybe have hired the way that they have historically. They're like, yeah, but it's working for me.

Ryan Stowers:

Right.

The Risks of Closing Off

Michael Horn:

What's the downside if they don't make the changes?

Ryan Stowers:

At a general level, we've seen examples of companies when they're unwilling to make changes that anyone looking at the landscape would say, hey, you need to change. So think of just out of the work and learning context for a minute. Look at Kodak, and remember, Kodak was the leader in their industry. At a time when they should have probably seen the writing on the wall, understood the landscape, and been willing to open themselves up to new ideas, new concepts, and new technologies. They shifted away from digital photography because they didn't want to threaten their profits from their film photography. And you think of the consequences of that decision. They were cataclysmic. For Kodak, they meant stagnation and eventually, ultimately failure. I think we're at a point where if you look at the US economy, you look at the number of jobs that are available and necessary in order to keep these companies moving, in order to help them produce products and services that make the world a better place, make people's lives better. Based on our current approach to talent, who and how we hire, and how we develop our people as employers. We've got a more closed system than would suggest is necessary in order to be successful in the long run. There are a lot of companies that are looking at changing the way they hire and changing how they develop their employees from a social impact standpoint. But I think what you and I are talking about is that they ought to be thinking about it from a business standpoint. For far too long, companies have relied on the proxy of degrees as telling them, for instance, what person they're finding in the marketplace and how that person is going to add value to their enterprise, their company. An over-reliance on something, sticking with the degree, in the long run, to help employers understand who they're hiring and what that person will be able to do in the company. This could be the Kodak moment for a lot of these companies because things are shifting. People are valuing things in different ways. There's so much fluctuation in the education market, the credentialing market. People are looking at skills now more than just degrees. From my perspective, they're not going far enough. How do we use technology and identify solutions that can empower employers to know exactly what they're getting when they hire somebody? Because there's a way to understand aptitudes and mindsets and gain skills and knowledge. To me, that has the ability to give a company a competitive edge in industries, especially where other companies are slower to respond in that way. To me, the answer for a lot of these companies, if they want to continue to be relevant, they'll change the way they think and act, and they'll approach all of their talent practices in a very different way. Understanding that their human capital, their talent, and their employees are the most important assets they have. Investing in them in ways that matter more to the individual, I think, is not just the right thing to do, it's going to be the competitive and smart thing to do as a business.

Michael Horn:

It's so interesting hearing you sort of develop that out. I get new things every time we talk about these principles. The one right there I got was actually openness, the opposite of it isn't just closed, it's a risk aversion. Right. In some ways, you often think of the HR function in a company as being very risk-averse. It's sort of the, no one got fired for hiring IBM back in the day.

Ryan Stowers:

That's right.

Michael Horn:

I like that Kodak moment language. You can almost imagine, I think, what you're arguing is you can stay with the same practices. You may have heard the Andreessen Horowitz podcast recently on Higher Ed where they were saying their companies don't just recruit from Stanford anymore because it turns out it's not a good predictor of success in the companies. So they're having to get more creative and look at different measures and assessments themselves on point because, in many ways, the degree is itself discriminatory and not very helpful to the companies. So as an HR leader, breaking out of those tried and true, quote, unquote, mindsets is important, perhaps to staying ahead of the curve, if I'm understanding you right.

Ryan Stowers:

Yeah, exactly. Look at some of the other problems they're facing. In addition to not being able to find enough people to fill roles, they're having a hard time retaining talent. In reality, the answer is the same. If companies will invest in people in ways where they're empowering them, where they're meeting them, where they are, we're seeing the data. I mean, paycheck and compensation matters, the commute matters, but so does purpose. So does meaning in one's career, even to the point where this younger generation seems to be willing to trade off some levels of compensation in order to find that purpose and meaning. A smart employer would tune into that aspect of the landscape and recognize that in order to stay ahead of the game, they've got to change their talent practices in order to hire the people that are going to want to contribute, to have that contribution mindset to achieving what the business wants to achieve. And I think that tweak is huge, Michael. I think it's going to matter a lot.

Michael Horn:

Yeah, I couldn't agree more. We're seeing the same data. As you know, I’ve got this book that I've been working on, and the data we see on individuals trying to make progress as they switch jobs is that the paycheck, it stands in as a proxy for something. It's a proxy for I want more respect or I have to pay daycare bills. So it's a proxy. It's not the root cause. We really need to get root causes and understand people's purpose and progress underneath it. To your point, as a whole individual, not just you at work. David Brooks had this piece recently on marriage being much more important than work for happiness.

The Effect of Openness on Individuals

Let's end our conversation here with individuals. What's the upside and downside for individuals if they are or are not in places that actually support openness? What should individuals be looking for and thinking about?

Ryan Stowers:

Yeah, there are a couple of different ways you could talk about this. If you step back and think about openness in the workplace, think about the difference between working for a company where not just your input from day to day, whether it's making devices or transferring information or whatever your role looks like. Think about the difference between you just kind of plugging in and doing your thing, versus an environment where your supervisor or the people on your team or your employer generally respects you for what you have to bring to the table and is open to your ideas. Given your local knowledge about what you do from day to day versus anyone else in your organization, the possibility of you coming up with ways to make that better, or make that more efficient, or make it more impactful or effective, and that kind of empowerment approach internal to a company, or that kind of openness to the possibility that a leader doesn't always know everything that's best about what's going on in the company. The learner worker in this case is learning through experimentation, learning through trial and error. He or she is respected and given the chance to share his or her ideas and thoughts and know that they're impactful. That kind of empowerment and openness in the workplace creates a much better environment and one that people want to be a part of. They go to work because they find purpose.It connects up with what we were talking about a minute ago. It connects with their ability to make something bigger than themselves better and move forward. They've got a sense of ownership in that improvement. They've got a sense of ownership in that innovation. So I think it has a ton of potential to unleash things in people that, frankly, we just haven't seen in the past in ways that are much more empowering and much more effective for both the employer and the employee. This gets back to a different level of mutual benefit than I think we've seen in the past. There are employers figuring this out. There are employers doing things differently right now. I think Walmart's taken a huge step in this direction, focusing on lifelong learning, focusing on the merits of understanding who the individual employee is, what their aptitudes are, recognizing that if they invest in people in these individualized ways, they're going to be empowered and want to contribute in ways that are much more meaningful and important to the company than otherwise. I think you're going to see companies that take that approach gain a competitive edge. I met with an employer last week, Martin Ritter, who's the CEO of a Swiss-based company that makes passenger train cars. And his US operations here in Salt Lake City. He came to the US and recognized this challenge. They weren't finding talent at the level they needed to, with the right aptitudes or skills, through the traditional system. So he approached a local community college and built a program that allows juniors and seniors to come into the company, and get credentialed for what they're doing in conjunction with what they're learning through the community college, as well as what they're learning through this apprenticeship program. They're hiring people because the people are more connected to what the company is trying to do.They're more motivated to be a part of it. They were met in a way that the traditional system wouldn't have met with them. In fact, in a lot of cases, there would have been barriers preventing this level of access. So in this instance, it's an employer fundamentally being open to more risk and fundamentally changing the way he thought and acted about work and learning. That's leading to improved outcomes for hundreds of young people in the Intermountain West mostly in Salt Lake City, Utah. So it's just an example. And you're seeing this. You're seeing employers start to step up and change. And, you know, the reason they're doing that is they know that it's going to give them a competitive edge and let them be more effective. In turn, it's going to help unleash the potential in their employees and workers in people.

Michael Horn:

I love that case study, and it's a great place to end because it really is the win-win. It's the positive sum as opposed to too often I think in society we sit there thinking, who's the loser in this? No, the individual benefits. The schools are certainly benefiting, and of course, the employer is in that example. Ryan, thanks for doing the work you continue to do and for joining us. We're going to find time in a few more months to catch up on what you're learning from the portfolio and continued evolution but just really appreciate it.

Share this post