John Woods, provost and chief academic officer at the University of Phoenix, joined me to discuss how the University is drawing a closer connection between college and career. We discuss steps the college has taken to build career pathways and equip students with the language and signals to communicate their skills. This episode is worth the read/watch/or listen, as all that they’re doing I suspect will surprise you.

Michael Horn:

Welcome to the Future of Education. I'm Michael Horn and I'm excited about today's show because we're going to get to geek out on topics that have just become more and more of interest to me as we think about where the puck is going in education, learning, upskilling and so forth, which is a lot about careers and skills and things of that nature. And so to help us navigate that conversation, delighted, we have John Woods. He is the Chief Academic Officer and provost for the University of Phoenix. John, thanks so much for joining us.

John Woods:

Thanks, Michael. And thanks for the hockey reference. That resonates with me as a Canadian.

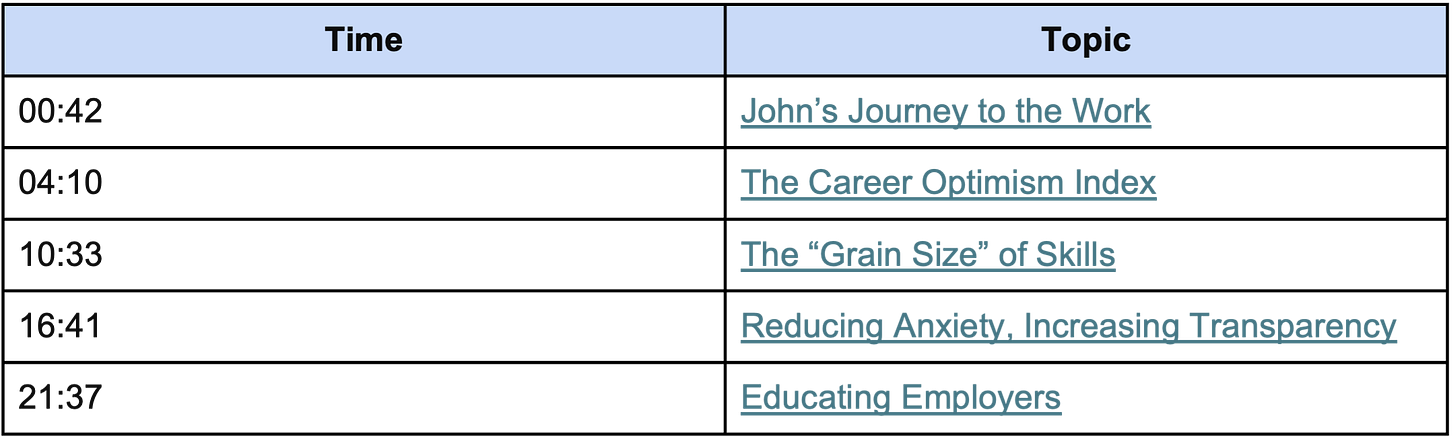

John’s Journey to the Work

Michael Horn:

There you go. And we’re trying to make you really feel at home, right? But let's start and make you feel even more at home. Before we get into some of these conversations around skills and careers generally, let's talk about your own career path to the University of Phoenix and perhaps reintroducing the University of Phoenix to folks. You and I got to spend some time together just a few months back and with a lot of the senior leadership team at the University of Phoenix. And it's clear to me anyway that it's a very different place from, say, 15 years ago, say a decade ago. So if it's easy to do, interweaving your own story with how the University of Phoenix has evolved and how you've landed as the provost there.

John Woods:

OK, so real kind of quick backdrop here. I've got a coal miners lamp on the shelf behind me, one of the many things on that shelf. Both my grandparents were coal miners and my parents, neither one of them went to college. I had two older sisters that didn't go to college, so I was a prototypical first generation college student. I was not a very successful student. I tell the story of my mother dropping me off and some upper class students grabbing my duffel bags and me waving goodbye. And that was it. And I was there for eight years. I don't think my parents visited the campus once. I did an undergrad and a master's and went on to do my PhD in higher ed, higher education administration. And I took a real interest in that because of my own experience in higher ed. And I did a couple areas of focus within my PhD work. One was adult learning theory and the other one was academic honesty. And I thought I would return to Canada from the US with my PhD in hand and go to work at a Canadian university. But I had a lot of opportunities in the US and stayed. I worked for about 25 years for adult focused institutions some eight years ago, I was contacted by the University of Phoenix when they were looking for a future provost and lucky enough to come on board there. Coming up on my 7th anniversary, I guess it would be soon and been part of this thing you just described, which is becoming a very different university. When I joined, new owners had recently purchased the university as well as a number of other companies within that same portfolio, and they sold the other companies off. Some of them were institutions in other countries and they really focused on the University of Phoenix, which had kind of a different model when it was publicly traded. There were not only these other companies within the portfolio, but there was sort of a central service providing really help to the different business units, including the University of Phoenix. And what they sought to do was really divest of all the other things and focus on Phoenix and push all the services back into the university to make it a standalone soup to nuts entity. And as well they decided that they were going to make a number of changes to improve the outcomes at the university. I've been part of that journey, which has been fantastic. I really consider kind of to be the capstone of my career, working with working adults.

The Career Optimism Index

Michael Horn:

Very cool. And obviously I think this is going to be a more natural segue than I had even planned with that backstory because obviously now you're making sure the education you all provide is not just academically rigorous, but it's also career relevant. And maybe career relevant is where you all start. And I don't think I have to tell you that it's unusual for a provost at a university to have that sort of focus and that be the portfolio sort of charge, if you will. But one of the things that you oversee each year is the Career Optimism Index. It surveys 5,000 American workers to understand their points of view and their sentiment on the labor market economy and so forth. And we'll be sure to link to the current version of it, the 2024. But I'd love to hear from your perspective, what jumped off the page. What were some of the highlights from this latest installment? Because I will say it was interesting to me that there seems to be a lot of tension in the market right now. That was one of the things that really came out loud and clear, but I'm curious if that stood out to you as much or what your big takeaways were.

John Woods:

Yeah. To connect some of the transformation at the University of Phoenix to the most recent findings in that survey, which I think there's just a wealth of good information in there and I'm glad you can provide maybe a link to it. We presented it to chambers of commerce across the country and a number of different organizations that are really interested in that data. So some good stuff in there. The transformation kind of, of the University of Phoenix included eliminating a lot of programs that we're not tracking to above average job growth projections. So that's where kind of this starts. And only adding new programs that met that criteria for a certain amount of growth that was projected in terms of jobs. And when I laugh a little bit sometimes when people kind of compare the size of the university to what we used to be and say the beleaguered University of Phoenix, which is much smaller than it used to be.

Michael Horn:

What is it right now? Like 100,000 or so?

John Woods:

We're over 80,000, but getting smaller was intentional. So moving away from campuses, because working adults had clearly chosen online as their modality of choice, moving away from programs that didn't track to really good job growth prospects, and then adding programs that only did that, those were big steps. And then probably the next biggest couple of things is we reduced the cost of attending the University of Phoenix in 2017 and haven't increased it since. I think I saw a statistic the other day that, on average, higher education has increased its price at a rate higher than the rate of inflation for something like 65 of the last 70 years. So we really bucked the trend there. And then we skills mapped every one of our programs so that when a student completes a course in their program at the University of Phoenix, they've earned a number of skills. But we clearly signal to them what the three top skills are that they've earned, and that skills mapping tracks from the learning content that they are exposed to, to the assessments they complete, to the data we collect, that tells us the level at which they achieved on those assessments. So how I connect this to what the Career Optimism Index survey tells us in its most recent iteration is that, as you said, not only do we survey a bunch of workers to get their sentiment on their career prospects, but we also, as part of that study, survey a number of companies, and we hear from them as well. And it's interesting to kind of see the points of differentiation between the two sets of populations and their perceptions. Companies are saying it's hard to find people, hard to find people that have the right skills, that they need. Workers are saying that companies don't seem to value professional development as much as they once used to, and companies don't do enough to develop their talent, to keep their talent, to grow their talent, and so that's an interesting, you know, kind of dichotomy, because the, the mapping of our programs for skills, we think, has given our students a language that they can communicate in with an employer or a boss or a future boss or prospective boss.

We've now issued 685,000 skills badges. The badges are collections of skills, and the students can post those instantly with a couple of clicks to their LinkedIn profile or zip recruiter profile. But more than anything, as I said, it's given them a language they can speak in that companies understand. And that skills mapping that took three years to do has enabled us not only to do that badge work, which I think is probably more badges than any other institution is issued so far, but we've also created a set of career tools with that same data. So one tool allows students in their portal to be sent actual jobs that match their skills profile with us. So the data is all connected that way that, Michael, I could send you three jobs and you'd see that you are an 85% match to those jobs, and you could apply or click on a link to get help to apply from us. And we think that's changing the game, because the notion of, I'm going to go back to school, and when I finish, I hope I get a better job, it shouldn't really be that way. The degrees and what people learn should be far more transparent, and people should be able to earn as they learn, maybe change their circumstances, not only at the end, but even as they go. But that can't happen with the opaque nature of a degree where people say, I'm done my second year, can you hire me? It can't even be done sometimes when they've got the degree in hand, because it's not clear what's in the degree. So we think this really can unlock some of that.

The ‘Grain Size’ of Skills

Michael Horn:

Very cool. So let's double click on the skills part of it and the badging and so forth. I'm just curious because sometimes employers have, like, really clear understanding of the skills that they want, and sometimes, as you know, they don't really have much clue, so. And you all have an unabashedly sort of both and approach to this, right, degree and skills, which I think stands out in a marketplace where, you know, a lot of places are all in on one or all in on the other. I'm just curious, can you give us a sense of, like, the grain size of the skills? And are you the one certifying them? Are they third party? And just so you know, the reason I ask, I was with a CLO of a large company the other day, and he was observing, “you know, I think we're sort of overthinking the skills conversation. We're trying to get so granular and specific that we sort of lost the plot,” was his argument. So I'm sort of curious your take and what grain size we're talking here.

John Woods:

Yeah. So I find it really fascinating. When any of these lists are published annually of the top skills employers are looking for, they usually come out from people like SHRM or the big consulting firms. Those lists always have what we'll call soft skills.

Michael Horn:

Yeah, the communication, critical thinking, which aggregates well across all skills and industries.

John Woods:

That's getting somebody who can really function and by their sheer nature being able to function while they're more teachable or trainable along the technical skill stuff. And so we mapped for that, too. And I think that's been really important, those types of things, executive functioning skills, some people call them. They exist in core classes and they exist in gen eds, and we've mapped for them too. So park that for a second, because I think those are really valuable and helpful, making people better workers and more promotable and all these other things. But the mapping we did of all the technical skills kind of took a bit of a Rosetta stone to build that, because the inputs were many and employers certainly wanted input. We have our industry advisory boards made up of companies that gave us those inputs, but we also have programmatic accreditors who say these things have to be in your programs for you to hold our accreditation. And then on top of that, we had all the kind of industry groups that weigh in on these things.

And then you actually had all of the jobs and their definitions from the Bureau of Labor. All the jobs have codes, and all the codes have a number of ingredients baked into them of what the skills should be. So we mapped all of that and saw that we taught all these things in our programs, but we needed to probably simplify to what you said and identify the top ones. So where, from all the source data, where are the things that people are asking for? What are those, the things they're asking for the most? So we rank them, and the top three are most clear, and those are the ones that we make more clear to the student, and it's collections of those that give students badges. Now, on the other side of the coin, to your question, we're doing an awful lot of work with employers, so we can tell employers this on behalf of our students and make them more interested in our grads but we also have some tools that leverage, and I know you wanted to talk a little bit about this today, but we have some tools that leverage AI, which will allow an employer to identify the skills being demonstrated by a group of people within their organization and map that up against. Maybe it's the next level position in that organization, that they've identified the skills for that job, and we can show them what the gaps are. And in that way, we could maybe do some just-in-time training for the people. They've got to be developed into these other roles, which is a lot less costly and risky than bringing on brand new people for those roles, plus more enfranchising for the people they already have to take an interest in their growth and development and show them a path to promotion. So we've actually got a couple of pilots going on with employers where we're doing that leveraging, like I said, some AI tools.

Michael Horn:

I mean, that gets cool, because I think what you're saying is the AI allows you to assess and skill in context, as opposed to pulling me out of my job. And as you also know, critical thinking, we use the same words in every field, but how it manifests in one field is very different from another. So now I can develop that critical thinking skills in the context of the industry I'm working for.

John Woods:

Yeah, and I think, you know, we hear an awful lot about employers and their frustration with higher ed. I think this can really solve for a lot of that. And, you know, I think kind of running parallel to their own skepticism of higher ed and some of the pronouncements some of the bigger companies have made, that they'll hire people without degrees, you know, no degree required, we'll train you. Running parallel to that, in the last year, we've seen 100 institutions either go away entirely or merge with somebody else. We know higher ed is costing more and more. We've seen dozens of institutions announce that they have big deficits, that they have to cut programs and even sacred ground, eliminate tenured faculty roles. So higher ed doesn't have a great brand right now of solving employer problems. And we think the combination of being more affordable and being much more granular, to your words, around what the student is learning and making that connection more clear, that people can speak to what they've got in terms of skills, employers can hear it and understand it and feel more confident. We feel this is kind of a recipe that is, it's time has come kind of thing, especially with what's going on in all of higher ed, as I described.

Reducing Anxiety, Increasing Transparency

Michael Horn:

Well, it's interesting. If you step back from that and you think about the anxiety that you described in the Career Optimism Index on both sides, the employees and the employers, one of the things it seems to me that you're doing is trying to strip out anxiety on all sides. right? We're not raising the price you've held at constant. You're trying to make the skills that you actually learn within the degree much more transparent. So you know where the matches are in the market, and then you're trying to do it within context so it's less of a step away, if you will. And I want to try this one out on you and see how you react. Someone observed recently, actually my co author on the upcoming book Job Moves observed to me that everyone sort of wants to rag on Gen Z for being impatient and looking for the next thing right away and so forth, and he's like, can you really blame them? All we do is sit there yelling at them that their skills are eroding faster than ever. Of course they're impatient to use them and put them to good use.

I'm curious, you know how that lands with the moves that you are all making and the folks that you're serving.

John Woods:

Yeah. And this one hits close to home, too, because I've got a grad, a college grad from, I remember that three months ago who's looking for a way to launch, and I need them off the payroll. And then I've got one in college who's trying to figure out what to major in. And right now she's, she's majoring in psychology and, well, I have to wonder where that's going to go. So we'll figure all that out. But the generation you're talking about, I think they need a better set of tools to navigate a really complex, rapidly changing work environment. And the frustration that they're facing when they talk to employers or prospective employers, I think, is that they're not speaking the same language. And I think the anxiety of folks on the employer side who could hire their way out of this thing can't anymore.

John Woods:

The labor market is pretty tight. Unemployment is pretty low. There's not as much churn as there was in previous years in the market. So just finding people to do the things they need to do is not easy. So I think they got to grow their own people, and they might have to bring more people in at lower levels and have great programs in place to engage and develop them. And the only way they can do that with any amount of specificity or accuracy is the skills kind of map the skills taxonomy, the skills pathway that I think we've sort of tried to unlock here. So we're really actually pretty excited. We can reduce anxiety in both those groups.

Michael Horn:

Yeah. And I forgot the other way you're reducing anxiety is by eliminating degree programs that don't have that positive ROI. And I'm going to get the number wrong, but I think it was Third Way that said, over a third of bachelor's degrees - right. - have a negative ROI after five years. I think Preston Cooper's research has shown, like, 25% or something, always have a negative ROI. Getting those off the table and being transparent about it, I think that probably helps a great deal as well.

John Woods:

And those numbers being well documented, if you put that up against the number, that seems to persist. And I wrote it down here for today, the New York Federal Reserve said that people with bachelor's degrees are earning, on average, $60k versus $35k for people without. If you think about that and the negative ROI and a bunch of degrees, it means there's a lot of degrees out there that are really helping people improve or change their lives.

Michael Horn:

That's a great point.

John Woods:

Yeah. And so what we try to, I think, make clear to folks is the degree over the long haul is still an amazing ROI. And if it comes with a couple of caveats, the school that's offering it should be able to tell you our degree because of the network you'll get at our liberal arts college. And another school will say our degree because there's a need for technicians who do HVAC or whatever it is. And we'll say it's our degree because it's practitioners who've done the jobs you want teaching it. And the skills that we've mapped into the programs, into the courses, give you what you need to, with confidence, share what you know, and employers will understand that. So everybody kind of, you know, across this vast landscape, diverse higher education institutions, they've got to have the, you know, the story that backs up what they are selling. And that's some kind of great thing about American Higher Education, is its diversity.

But the stories are being challenged, so you got to back them up.

Educating Employers

Michael Horn:

Yeah. And I love the way you just framed each of those narratives for three very different universities in very different parts of the stack, if you will. Last question for me as we start to wrap up, which is you've talked about growing your own and the reskilling or upskilling that employers have to do. I think that's right. Some people worry, well, will they go to another company. And as Richard Branson, I think, quoted once said, yeah, but what if they stay at yours and you didn't upskill them? So I think it makes a lot of sense. The curiosity I have is you're introducing the skills, taxonomy and language so that people, employers and employees, or prospective employees in some cases, can talk with each other better and make these matches. How much education are you having to do on the employer side? And the reason I ask is, my observation at least, is they do have a pretty good grasp of the core technical skills that are at hand in any given job.

And then the critical thinking, communication and stuff like that. They know it's important, but they don't really know how to measure or assess or like what it really means in their context. And so I'm curious how much education or to get them to buy in, if you will. You all have to do on that with sort of the leadership role you have to play?

John Woods:

Yeah. The interest we've had, when we share what you and I just talked about for a few minutes, the interest is really high. It comes in within an environment of a lot of people talking about skills-based hiring, maybe more than I've ever heard talked about. And like you said, the proof is in the demonstration of the skills, whether they're technical or executive functioning, soft skills, durable skills, whatever you want to call it. I think what we've been able to do is show them how we assess those things, how they can assess those things. I think that will be an evolution. I think we'll get better at that and they'll get more receptive to that. And I think the driver for that is the sheer economics of it. Many of them are already paying for their employees to go back to school as a retention tool because some other employer will offer it if they don't. They want that to make sense for them and for the learner. And making sense means they'll stay, they'll be increasingly more valuable to the organization. So those economics all work far better than we had. X number of positions we couldn't fill for a long time, and they were vacant, and as they were vacant we were hurting from it. Or we filled x number of positions, but a lot of them flamed out of or we hired a bunch of new people at a tremendous cost. We wish we didn't have as much churn and need to do that.

John Woods:

The economic drivers are at least those and many more for folks to be open and interested in this concept, in this conversation. So I think it's for those reasons we've had great conversations with companies and are helping, we think, kind of solve some of this challenge for them.

Michael Horn:

Yeah. So actually I lied. I want to ask one more question about that because it's so interesting. I guess my observation then out of that is like you're basically tagging these skills to a much clearer KPI's so they can understand the ROI with much more granularity perhaps than past education investments they've made. The flip side of that, I guess, is as you're starting to show them how you assess it, can they start building that into their own performance management systems to better show the growth of their employees and where they need to work?

John Woods:

Yeah, I think that's possible. I think in a couple of really far along conversations we've had with companies, we've talked about doing exactly that as kind of follow-on work. Step one would be we have people we can demonstrate, have the skills to the jobs you've got today. Just need to give them that opportunity. We're confident we've got the skills right for what you have. Second part of the conversation, we think we can assess the skills of the people you've got and get them to different positions within your organization, not even maybe with whole degrees, but with courses or certificates. And as you said, the third part of the conversation would be kind of following those people along and being able to measure the actual demonstration of skills that we all kind of bought in and thought would happen and seeing where they go over time. And I think we'll get there. I think AI is going to be instrumental in getting there. There's a lot of way to evaluate different kinds of work product and use inference and some of the large language models to inform what is versus what is not in terms of the work product. So we're excited because that's only evolving and at a rapid pace. We think these conversations can get even better. We're excited about where we are, but we think there's a lot more to come.

Michael Horn:

Very, very cool. I mean, I love the transparency, careers making skills a real currency and lingua franca, if you will, on both sides of. John, huge thanks for joining us and talking about the approach that the University of Phoenix is taking on this.

John Woods:

Thanks, Michael. Enjoyed talking to you and happy to do it again, maybe give you a ere's the rest of the story down the road.

Share this post