Tutoring has been a favorite intervention among school systems looking to get their students back on track after the pandemic. But not all programs are created equal. Results have been uneven at best.

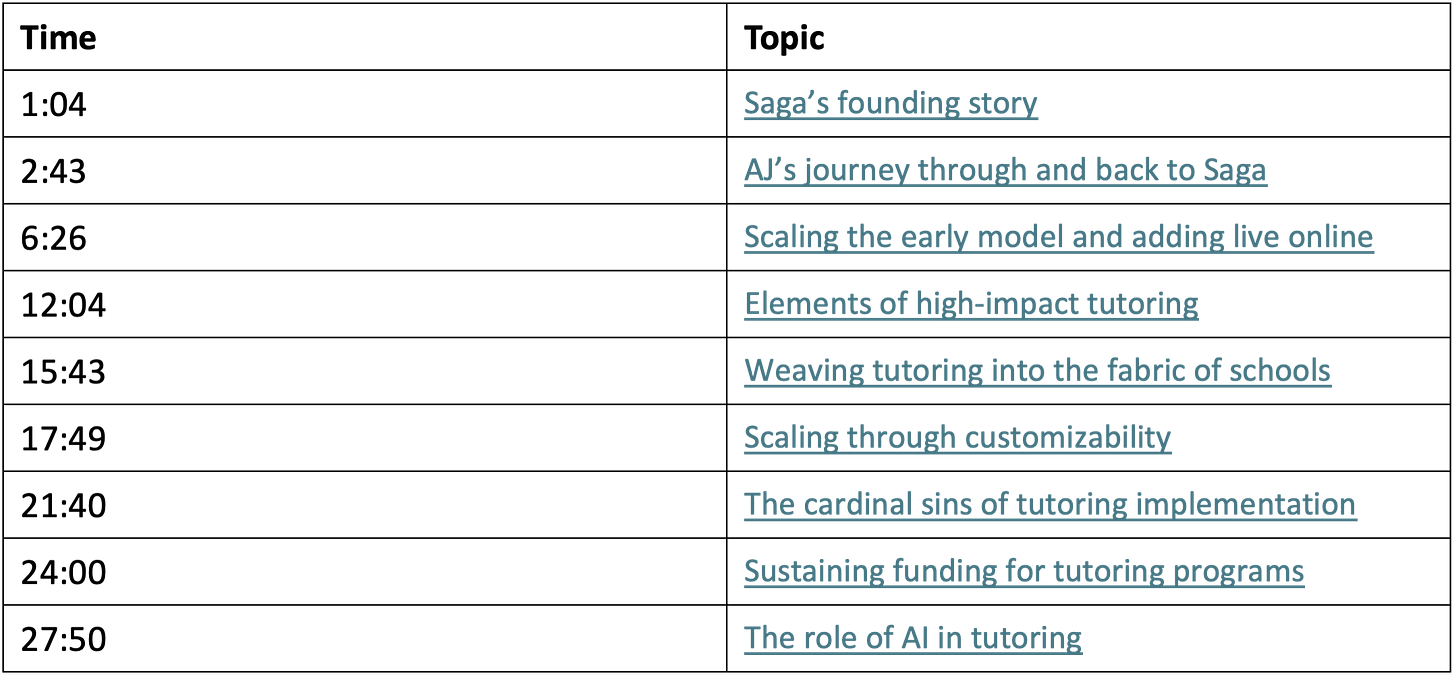

I sat down with the Alan Safran and AJ Gutierrez of Saga Education, a nonprofit that has been supporting schools to get tutoring right since long before the pandemic. We discussed the evolution of their model, what it will take to weave tutoring into the fabric of schools, sustaining programs after federal COVID funds are depleted, and the role of AI in the future of tutoring. As always, subscribers can listen to the podcast, watch the video, or read the transcript below.

Michael Horn:

Welcome to the Future of Education. I'm Michael Horn, and you are joining the show where we are dedicated to building a world in which all individuals can build their passions, fulfill their human potential and live a life of purpose. And here to help us think about that are two co-founders of Saga Education. We have Alan Safran and AJ Gutierrez. Alan serves as the CEO and AJ is the Chief Policy and Public Affairs officer. But as we'll hear, Saga has been at this work of tutoring long before the pandemic made it a trendy topic. I remember meeting with both of them outside of Porter Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. We had a great conversation about all the things that they were learning about how you do tutoring well, how you start to think about scale and a lot of the questions that were on their minds.

So, Alan, AJ, great to see you. Thanks for coming back and educating me once more.

Alan Safran:

Yeah, great to see you again.

AJ Gutierrez:

Yeah, it's great to be here, too. And usually after meeting us for the first time, people don't want anything to do with us. So I'm actually surprised and excited to be here.

Saga’s founding story

Michael Horn:

When you reached out, I was like, yes, I need an update. I want to know what's going on, but fill our audience in first. And Alan, I'll start with you. What's the founding story behind Saga Education? Because it has an interesting origin story that is perhaps not what most people think of when they think of tutoring.

Alan Safran:

We go back to Aristotle and Socrates thinking about individual tutorial, but a little more modern. I was Executive Director of the Match charter school in Boston. AJ was a 9th grader when I first met him at that school, and Mike Goldstein was the founder. And Mike had the idea, look, kids are coming to school like AJ and his classmates, many of them three years behind grade level. What do you do when you're a normal school with a normal schedule, with normal classrooms? You can't do it. A teacher, no matter how heroic, has a hard time differentiating in a class, say, at 9th grade, where there's an 8th grade differential between some kids coming in like six years beyond grade level and other kids coming in two years ahead. It's impossible. The burden we put on teachers.

What the expectation is for teachers to reach grade level skills is impossible. So how do you structurally address that? So Mike had the idea, let's build a dorm in our building. Bingo. Let's recruit tutors from around the country, like Teach for America recruits teachers. Let's recruit tutors. He said, what I think of the idea, I thought it was crazy. But then we worked together. We started it in 2004 and within a few years we had a reputation.

The US Department of Ed said we were in the top seven charter schools in the country. And the results for kids like AJ were remarkable. And my own story is I come from two public school teachers, so I long have had in my blood this desire to get justice for kids. It's a phrase not often used for teaching, but getting justice for kids whom the system has not provided enough for. For me, that's a big theme of my life. And AJ's origin story is even more interesting than that.

AJ’s journey through and back to Saga

Michael Horn:

AJ, why don't you give yours and how you go from a 9th grade student, the beneficiary of this tutoring model, to starting an organization to think about tutoring more widespread, not just in match education.

AJ Gutierrez:

It's certainly been an extraordinary experience for me, just working alongside Alan, who's known me since I was a 9th grade student and he was my chess coach. For me, it's such a pleasure to bring a model that had such an impact on my life to lives of students internationally, not just in the United States. We've had some exciting work and research done in the Netherlands, for example. But as Alan mentioned, it was really game changing for me. When I was entering 9th grade, I was really disconnected from school as a c minus c plus student. I grew up with a single mother with three kids. And for the people who are listening, who are parents, you know how hard it is to keep up with day to day. Can you imagine working multiple jobs and trying to stay connected to what's going on in school? And that's exactly what's happened with my mother.

And every year just got harder and harder. And so when I attended Match, I had a chance to work with the tutor, it was really game changing for me. But as I look back at that experience, I don't really think about it from an accelerated learning perspective, although that was really important. But the opportunity to really connect with someone in a meaningful way who knew my name, who knew my birthday, who communicated with my mom, was so amazing to me. And for my tutor, getting to know his life story and really discovering there's just so much that we had in common was really important to me. So it matched. As Alan mentioned, it had a lot of traction, success. Some other charter schools replicated the model and we had a chance to work to see if we could bring this model into traditional district school settings.

And that was at the early stage of my career in education and I was kind of thrown into the frying pan because the first time we tried to replicate this work was in Lawrence, Massachusetts, when it was under school receivership. So the state took over the district due to academic performance reasons. And at that moment, it was the greatest turnaround in high school math in Massachusetts state history on the local state exam in terms of what they call the student growth percentile. So that was a really great indication that we could be onto something here. And roughly around that time in 2011, the University of Chicago Education Lab was conducting randomized control research studies on a social cognitive behavioral therapy program called becoming a man, which was the catalyst for My Brother's Keeper initiative for President Obama. And they wanted to see if you can couple this cognitive behavioral therapy with really intensive tutoring. And so we work with them as part of several randomized control research studies, which was, at the time, really encouraging. It was one of the most significant academic gains I've seen that's been rigorously evaluated in US public education.

You could double or triple math learning compared to students who didn't receive tutoring. We started Saga to continue, explore how we can develop and scale this approach. I mean, everyone knows tutoring is a great way to help kids. What's the first thing you do once your child starts falling behind academically? You get a tutor for them. And so the question is, like, how do we give access to this type of resource to families and students who wouldn't otherwise have had access to it? And so, as we try different models and permutations, try and understand the impact through rigorous randomized trials like the gold standard for research.

Scaling the early model and adding live online

Michael Horn:

So stay on that for a moment, because you've done a ton of research, as you mentioned, through the various iterations, you've had. The base Saga model, and I know you've iterated it in recent years, but coming into the pandemic, the base model that you all had, describe what that actually looked like from a student and tutor perspective in terms of the time, relationship, and number of other students may be with them or not, and so forth. Just let's be super clear about what this looked like.

Alan Safran:

Let me take that. So the base model had two permutations I'm going to highlight. One was the classic, the Coke classic. One tutor across two kids, live in a classroom, no technology, build relationships, have the kid in front of you every day of the year. It's a period on the class schedule, in the 9th grade schedule taken out of an elective period, or for some other time. And that was it. That got the results of the University of Chicago published from the 2013 to 15 study of 0.26 standard deviations, which is up to two years of extra learning. Up to two and a half years of extra learning in one year.

That was the base model. We varied that before the pandemic and had a tutor across from four kids. Now they weren't tutoring four, they're tutoring two. The other two were working on an adaptive practice tool like Matthia or Alex or Khan, something practice. They tried to get the tutor's attention. Tutor said, look, you'll have me tomorrow because the next day the kids on the platform will get the live. Kids on the live will get the platform. The idea of that cocktail was use the relationship of lifetime to motivate the kids to take the tech time seriously.

And if they take the tech practice time seriously, they generate data that's useful to the tutor in the live time. So we went to that model. University of Chicago also evaluated that recently published results, same effectiveness at about 60% of the cost. So we were already driving down price. Keep maintaining impact. And even before the pandemic, we had a third flavor, which was live online tutoring. College Board challenges said, look, you should look at live online. We don't know why.

[We] said we'll look at it. We did an RCT in Chicago and New York and showed exciting, dramatic results for just 20 hours of dosage in a live online environment. So Dave Coleman, the CEO of College Board then and still was perspicacious. I don't think he knew that COVID was coming, but he knew something was real about live online. Wanted us to test it and we found it pretty valid and it's going to be important to the future of tutoring.

Michael Horn:

Stay on that for a moment. The live online, because I think that's where we'll just say, like, the pandemic took off. Everyone got excited about tutoring as an answer to all of the challenges, whatever you want to call them. The learning that was lost out on during that time and online was a big part of it. A lot of those, as we know, have not delivered. So when you say live online, what are the features of those? I think you said 20 hours a week or something like that. I'm not sure what you just said, but tell us features like how much time are we really talking? Is it the same person every single time? What are the features? How many other students, et cetera?

Alan Safran:

Yeah, so I should clarify, when we say live online, we mean a live human tutor. By the way, we talk about AI and bots in that, but for now, it's live human tutor interacting with a kid in the vertical environment of a platform as opposed to the horizontal table that we sat at in person world. So we did live online trial. It was 20 hours of dosage in that trial with the college board on the SAT, but now live online that we do in New York City. It's our model. In Chicago, some of our schools and others of our schools, it is at the same pace, same frequency. It's a class on your schedule. Whether it's one day a week or every other day, it's a class on your schedule.

Your tutor comes into your platform live, and you build a relationship with that tutor. The ratio is roughly the same. The training of the tutor is the same. The qualifications of the tutor is same. The labor force, though, is dramatically bigger than the ones you could find down the street from the school. That's why I have written a piece with Bob Runze, head of Chiefs for Change, recently in EdWeek, that said, look, the labor issue is going to be a big limiter to the potential to scale tutoring to what we think are the necessary focus, which is 3 million kids. We need 100,000 tutors to do that. Live online will open up that pool.

You can either draw a circle around a district school with like 20 miles if you want to have neighborhood live online, or you can go nationwide. You can go global if you want it. But let's say nationwide, the pool is so big that you'll be able to be selective in the tutors you hire. So on average, with a bigger funnel, the quality of tutors hired through live online will be better on average than the ones you can find in person locally. We think it's a piece of the future of education, in particular of tutoring.

Michael Horn:

Super interesting. Let me just make sure I got this straight. When you've studied it, are you still seeing, I think you said point two six standard deviations. Are you still seeing something like that?

Alan Safran:

We don't have an RCT on live online yet. We have some quasi experimental results on live online. We have our own internal measures that we actually have measured because we run programs now in four cities. It's not a big part of what Saga does. What Saga really does is help states and district to build their capacity. But in our four cities, we have some live online models and some in person. We've compared them on our internal measures. Very little degradation in student outcomes.

Hard outcomes like academic soft outcomes like student engagement and student belonging, and much higher tutor satisfaction in the online environment, which leads to tutor retention and less attrition so very encouraging. Early signs in live online. We're going to get a quasi-experimental design out of New York City with Jim Kemple of NYU's center analyzing propensity, matching set analysis retrospectively and current year, and I'm looking forward to the results of that. I'm optimistic that lava line is pretty good. It'll get better as we do it over time and as the country is starting to do it in some states like New Mexico and some districts like Ector County, Texas, which I visited just recently, it can be effective. It's got to have some key elements though.

Elements of high-impact tutoring

Michael Horn:

Okay, so let's talk about that then. AJ, turning to you, because we talk a lot about high dosage tutoring or high impact tutoring, there's different phrases right for it. What are the critical non negotiables that you all have discerned that need to be there for the tutoring to be effective?

AJ Gutierrez:

Yeah, many of the people listening to this right now are probably wondering what we mean when we say high impact tutoring. And usually when you think about tutoring, it's like homework help or after school. What we're trying to do is encourage people to think differently about it, where it's just part of the fabric of school design, where it's part of the regular school day, it's integrated to what's going on, it's aligned with what classroom instruction is. The tutor works with his or her student consistently throughout the year, maybe two to three times a week. Do you best keep those parents consistent and you provide coaching and ongoing feedback to tutors the same way we have those expectations for our teachers. And Phil, when Saga in the early days in our thinking around this, we were so fired up about the research, we're like, yeah, we're going to serve 20,000 students directly. We're going to keep growing. Pandemic comes along, flips k twelve education on its head.

We're really eager, but we just noticed there's just a dramatic need. And after having conversations with folks at the Bill of Melinda Gates foundation and Overdeck Family Foundation, we just recognized that given the need, we can't possibly scale to serve this directly. And our thinking really started to shift from the spirit of trying to replicate to a much more practical approach for scaling evidence based programs that's focused around adaptation. And what we're trying to do is empower schools and districts to implement high impact tutoring on their own. So what is it that we can do to provide them the resources, tools, technical assistance so that they can do that and trying to understand whether districts can do this effectively on their own, what student outcomes look like, what are the steps necessary to transfer what we know to be best practices to districts? And what we've discovered is that high impact tutoring really is a framework, it isn't a model. And there's a lot of opportunities to play around with different concepts, including thinking about ways you could integrate artificial intelligence to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of tutors. And there's so much that is worthy of exploration and I think we're excited to be part of the exploration. And lots of other merging organizations also are thinking about this issue and we're going to continue to share those insights.

The University of Chicago has a large-scale randomized trial in multiple school districts. Right now there are about 16,000 students who are part of this RCT with aspirations for this to increase even more. And it'll be the largest randomized trial on tutoring that's ever been conducted nationwide. And the early data on that is really encouraging and suggests that districts can do this. And that's really good news from a scale perspective, because if we can make this part of the fabric of school design at critical growth years, you don't have to provide a tutor for every single student, every grade. You maybe can create the conditions where as part of the K-12 experience, maybe students can have one or two years of really intensive personalized support to keep on track for graduation.

Weaving tutoring into the fabric of schools

Michael Horn:

So I want to stay on this. We'll go to the technology and AI toward the end, I want to come back to that. But what you just said, that you are now increasingly playing really a support function in the ecosystem to make sure that districts, states, schools are putting the right conditions in place so that whatever model or form of high impact tutoring that they put into place, that it'll be effective, that they can be confident that it's actually going to help students make progress in line with what they hope. Just say a little bit more about what that work actually looks like. And does that mean you're helping districts or schools pick out which tutor provider to work with? What does that actually look like? AJ, let's stay with you. And then, Alan, I'm going to flip in a moment to what this looks like in the school design itself, but I want to stay like at the level of support and helping them stand up these programs. What does that really look like?

AJ Gutierrez:

Well, Alan's like Mr. Miyagi right now. It's like wax on wax off, with the district leaders, I mean, that's something we're exploring now, what does it really take to help districts get this right? And we're really excited about that. It's really tricky. It's really complicated. And the interesting thing is, what we're trying to figure out is with Saga, we can gain as much as, like two and a half years of math growth. But even if a district could get half of that or a quarter of that, I mean, that's still game changing and that's still really exciting. And so I think part of the work is really providing hands-on support with program design and implementation, giving them access to things like our curriculum.

Some of the technologies we're using help them think about, how do you schedule this in the regular school day? What is providing training for the managers of the tutors? Providing the training for the tutors checks for fidelity, observing the tutors and providing feedback, just to name a few of the ways we're providing support to.

Scaling through customizability

Michael Horn:

No, that's super helpful. Okay, Alan, I'm going to turn to you here because I think the first time we met, I was like, yes, finally, someone's thinking about bringing the best of tutoring and scaling it. Because as I think about it, from a disruptive innovation standpoint, as you know, disruptive innovations get their start in areas of non consumption. And by my estimates, some 80% of students weren't getting the tutoring that they needed when they needed in this country for different things. And so you seem to have started to come up with some secret sauces that allow us to scale this more and more right online, one to four alternate days, different things like that. How do we start to weave this now into the design of schools themselves? Because, as you know, my passion has been how do we make schools places that can truly personalize in the right ways for an individual child whenever they need it, as opposed to thinking that they all need the same thing on the same day just because they have the same birth year.

Alan Safran:

Yeah.

Michael Horn:

So what does that look like?

Alan Safran:

Yeah, I'm better on this over a couple of beers and wine, but I'll try to condense it to a couple of minutes without the alcohol. So it's hard. It's a big battleship out there, the American public school system, 55 million kids turning that around really hard. So you got to get buy in. Buy in will come locally when people locally...And this starts with parents, by the way, I think. Parents, the major secret sauce here. Parents of kids who got tutoring in these Covid years and are at risk of losing tutoring for their next child who's coming up the pipeline, parents of multiple kids become a secret force to drive tutoring's continuation.

So turn the battleship around. You've got to get buy in from parents. You've got to get buy in from teachers. Fairfax County, Virginia, great example of this. They came to us, a group called J. Pallet of Cambridge introduced us. We went to them, said, look, we'd like to help you. They hired a district wide coordinator, terrific guy named Joe Ash, and he said, look, we want to do this, but I want to go slow.

I want to hire a principal who knows the work. The schools know him. He'll go school by school. Get principal, buy in. Give him a month to talk to the teachers, like, work it out, get the buy in. That's number one. You get buy in, then you start it small. Matt Kraft has said, start slow to get big.

You got to start tutoring slow to get good. There have been example[s] of starting big that still get results. Big city in America. But the better strategy. They started with one school in Fairfax. They have 130 now in a two year period. So start slow, get buy in, show results, show excitement. Now, I visited Fairfax, Orange County, Florida, Hector County, Texas, in recent weeks.

Now, the teachers say, I can't live without this. And here's what happened. The buy in comes not from getting a vendor necessarily. They don't know. They don't know the tutors. They don't know how they're selected. But maybe have the district put the tutors, whatever they are, whether they're district hired or vendor hired, into the teacher's classroom. The big worry, I think, by teachers here is that tutors are going to, we've heard this earlier, tutor is going to replace you in your jobs.

Well, no. Tutors are there to do two things which very few interventions accomplish. They support hardworking teachers who need help in differentiating and personalizing, and they support kids who are not getting their needs met because of the lack of structure that allows for teachers to personalize. So tutoring is an intervention that serves both the most important constituencies in education, which are the kids and their teachers. Building into the classroom is what Fairfax did, Orange county did, and it's not what we did. Talk about adaptation. Our model is not being replicated. We're not looking, as AJ said, for our model to be replicated.

We're looking for the framework, the framework as AJ described it. But let them vary it. Like, let them go to a different pool of tutors. They're going to part-time tutors. We tend to have full-time tutors. They're going to build it as part of the classroom. We tend to be our own classroom. A thousand flowers can bloom here.

But the way to turn this battleship around to scale this is to solve the time, people and money factors. We have answers to that. But initially to get the buy in from the people on the ground, that it's not being imposed on them, that they're going to have choices in the model here. But there are some key conditions that we know will lead to a better likelihood of success.

The cardinal sins of tutoring implementation

Michael Horn:

When the practices have gone off, what are the cardinal sins, to your point? And I couldn't agree more. Start small to go big. That's not always been the way of districts.

Alan Safran:

Right. Well, they're balancing the urgency of now, the fear surge.

Michael Horn:

They're balancing urgency of now, equity. There's a lot of things for sure, but when you say that, just what are the cardinal mistakes besides the we started all at once or something like that.

Alan Safran:

There's three. There have been three. We saw. One is they've asked their own teachers to do the tutoring. Teachers are broke...Their backs are breaking. Now even offering them $30, $40, $50 an hour to buy out their planning time, and I've seen this in a big city in America, is a disastrous pathway. It will break the back of teachers.

They will not succeed and it's not sustainable. Second big mistake was hiring, putting tutoring after school and on demand. That's not tutoring, that's just homework help. Like there's a company called paper. They're out of school time. They're offering the most. They say it's the most equitable because all kids can access will. Very few kids do access it? The ones who do or tend to be more motivated.

And we want to access the kids support the kids who are coming to school and meeting us halfway by showing, going up who are far behind grade level, not the kids who are highly motivated, whose parents could otherwise pay for it. So doing it out of school time, homework help was the second cardinal sin. The third is again, like just going too fast, too soon. But the way they decided to go fast, in many cases, knowing the labor force was limited, they said, look, ten to one, we'll be tutoring ten kids per tutor. Texas has that as a statute. There's some states that have five to one as part of the stats. That's wrong. Ten to one is not tutoring.

You're not going to find the pool of people who can handle ten kids at a time. You could find people. This is one of the great conclusions by the University of Chicago. The skills that it takes to be a tutor of one, two, three, or four kids are far different from the skills of tutoring class of 25 or 30. When you make a ten to one or five to one, you create a conditions in which the tutor is not going to succeed and then the initiative is not going to succeed, and then kids are not going to succeed, and we've failed. In another ed reform initiative, you got to start it with ratios of tutor to kids that are manageable by that labor force, not go to one to ten. I understand why it was a way to save money and to reduce the number of laborers you need, but it's not tutoring.

Sustaining funding for tutoring programs

Michael Horn:

Got it. That's super helpful. One more question on this, because you mentioned money as part of the equation, and obviously the thing that I think a lot of people have been worried about is federal funding that came in in the wake of COVID that a lot of it has gone to tutoring. We know it's drying up. So where does the money come from to be able to continue to support this on an ongoing basis?

Alan Safran:

Yeah, there's one more painful way, which is to repurpose what schools already get. Schools get lots of federal funds, about 5% of the budget, but it's about 1000 per pupil, steady state title one for schools that are serving high poverty kids, that's certainly enough money to provide a high impact tutoring program of quality. So repurposing some Title I dollars for the subset of kids that we say in grade three who need help getting over the literacy bar, and in grade eight or nine who need help getting over the algebra 1 bar. District has huge pool. Take a piece of it, fund tutoring efforts there. That's hard because they've got to unfund what they're already spending. Title one dollars are on. That's the harder one.

The easier one is find new federal funds that are replacements for the departing federal funds. The two best sources of that will fund the labor force at 80% of the cost of tutoring is on labor. The tutors, AmeriCorps, state commissions for Americorps have money. They distribute it every year. It's an application process, and they have made a priority of looking for high quality tutoring programs to fund. So a district can become an Americorps partner or a vendor can become an AmeriCorps partner. It becomes a subsidy for the cost of the wage.

Nearly all the cost of the wage of a tutor will be covered by federal AmeriCorps funds. The money is there. The second piece of federal funding is federal work study college undergraduates. Here's a set of kids who receive financial aid, subset of kids in college who receive work study as part of their financial aid, separate from grants or loans. They get a work study, have to work for the money. The college gets federal work study dollars. It's been around for 25 years. They fund the kids to get jobs in the community.

And one of the priorities now of the federal work study office is tutoring programs. So if you're a district, say, look, I want 20 kids from the local college down the street or 30 kids from the local community college down the street. If they're getting federal work study dollars, it'll subsidize 50% to 90% of the wage of those tutors. The tutors will get good money, say $20 an hour for a college undergrad, maybe 25. The college could subsidize 90% of that if the district negotiates hard. And we did that back in Boston in 2002, we had MIT saying, look, we're doing 90%. Harvard said they do 75. I said to Harvard, look, MIT is doing 90.

Okay, Harvard did 90. So you create a little competitiveness that only works in neighborhoods where if you're going live in person, you've got colleges to tap from. If you're rural America, again, you're going to have to go live online. But again, with colleges in rural America to become a source of labor subsidized by federal work study. So we think it's existing funds, federal title I funds, new federal funds, Americor and work study. And the final piece is just rethinking what a school does. You've written a book called from reopen. To reinvent, schools need to reinvent what is school.

School doesn't have to be only teachers. A class of 25. Throughout the day, it can be different set of people, adults working with kids. ASU, Arizona State is doing great thinking on this. Brent Bannon, I recommend him for his work. But a pool of tutors, who supports teachers and actually, the payoff here is financial. The return on investment is financial. You hold on to kids at grade three, literate kids, they graduated a four times graduation rate nine years later.

You hold on to kids to pass algebra one. They graduated a four times graduation three years later. And since school, local and state funding is tied to kids who are enrolled in your school, if you've lost them as a dropout at the end of grade nine, you've lost three years of their future funding, $45,000. Invest 1000 of your title. One dollars at grade nine to get some insurance that more of those kids will graduate. You've made the correct financial decision. That has a better ROI than anything else studied.

The role of AI in tutoring

Michael Horn:

Super interesting. Okay, as we start to wrap up here, AJ, you talked about technology. You mentioned AI. Alan, you talked about how if you pair technology alongside of the tutoring and create this reinforcement loop, what are y'all imagining right now? Could be on the horizon. Obviously, Khanmigo captured a lot of imaginations. I will tell you, Sal gave me an early license on it. I put one of my kids on it when she was home sick from school one day last year, and she was coding by the end of the day, it was pretty cool to watch. But what are you all dreaming up? Is an appropriate use of these technologies coming on the horizon to boost the sorts of effects you're seeing? Oh, AJ, you're muted.There you go.

AJ Gutierrez:

It's a super exciting time we're in, in education with the dawn of artificial intelligence. And there was a really interesting McKinsey study where they looked at consultants on the lower end of the bell curve, giving them access to AI. And at the end of the day, those consultants actually outperform some of the most know McKinsey consultants. And I think a big takeaway from that is that these types of technologies can supercharge human beings, and so now becomes more important than ever, I think making sure that people have access and know how to use these tools effectively, because it could exacerbate inequities if only a subset of our population knows how to use them effectively. But with that in mind, I think these types of technologies can supercharge our tutors. I can imagine a really interesting study on combining tutoring with Congo and what kind of outcomes you can get. Maybe a tutor can serve more students. Maybe it could be more prescriptive in providing guidance to tutors on how to be effective.

Maybe it reduces the amount of prep time it takes. And so these are some of the things that are worthy of exploration that we're really excited about. The most sophisticated AI project we're working on right now is in partnership with the University of Colorado School of Mines, where we're looking at developing a scalable way to provide ongoing coaching for tutors. And from our perspective, that Saga is really the secret sauce, I think, for success. And this technology can provide coaching and feedback just as effectively as an expert observer on a set of instructional strategies. And we think that's a really great way to supplement ongoing coaching. And what it does is look at the discourse that's taking on has affective analysis of different emotional states of students and what's really causing engagement, what kind of moves that tutors are doing that they're leading to understanding. And so that type of information, I think, could help us get a sense pretty quickly the quality of tutoring that's happening, but also be really prescriptive in how we support tutors.

And so that's some of the ways in which we're excited about how these technologies can really transform how we think about the scale of this type of resource so we can support more students.

Michael Horn:

Very cool, Alan. AJ, thanks for the continued work and rigor you're putting behind the work to make sure that what we do is actually helping students make progress. Appreciate you both. And in a couple years, when you have some more insights on how technology further changes or doesn't this game. Either way, whatever you learn, love you to come back on and inform the audience.