Putting ChatGPT to the Test

How Should Students and Educators Interact with Artificial Intelligence?

For all the speculation about ChatGPT’s potential to upend K–12 writing instruction, there has been little investigation into the underlying assumption that the AI chatbot can produce writing that makes the grade.

and I put OpenAI’s ChatGPT to the test by asking it to write essays in response to real school curriculum prompts. We then submitted those essays for evaluation. The results show that ChatGPT produces responses that meet or exceed standards across grade levels. This has big implications for schools, which should move with urgency to adjust their practices and learning models to keep pace with the shifting technological landscape.In a new piece for Education Next titled “To Teach Better Writing, Don’t Ban Artificial intelligence. Instead Embrace It,” we detail what we learned. You can read the article for free here, but here’s a bit more of the summary.

When it burst onto the scene in November 2022, ChatGPT’s clear and thorough written responses to user-generated prompts sparked widespread discussion. What it might mean for K–12 education was one area of speculation. Some worried about the potential for plagiarism, with students dishonestly passing off computer-generated work as their own creative product. Some viewed that threat as particularly formidable, pointing to three attributes that make ChatGPT different from past tools. First, it generates responses on-demand, meaning that students can receive a complete essay tailored to their prompt in a matter of seconds. Second, it is not repetitive. It tends to answer multiple submissions of the same prompt with responses that are distinct in their arguments and phrasing. And third, its output is untraceable, as it is not stored in any publicly accessible place on the Internet.

Education decision makers are already moving to respond to this new technology. In January, the New York City Department of Education instituted a ban on ChatGPT by blocking access to it on all its devices and networks. Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and Baltimore school districts have imposed similar prohibitions. As leaders in other districts, schools, and classrooms grapple with if, when, and how to make changes in response to this technology, they need a read on how well ChatGPT, in its present form, can deliver on the threat it is purported to pose.

To help answer this question,

and I took three essay prompts per grade level from EngageNY’s curriculum for grades 4 through 12, which are the grades in which students produce long-form essays. For each grade level, the three essay prompts covered the three main types of writing —persuasive, expository, and narrative—that students do. The tasks ranged from creating a choose-your-own-adventure story about an animal and its defense mechanisms to selecting a central idea common to Robert Browning’s poem “My Last Duchess,” William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, and an excerpt from Virginia Woolf’s essay “A Room of One’s Own” and explaining how the texts work together to build an understanding of that idea. We then asked ChatGPT to produce an essay response in the voice of a student from the respective grade level. With the essays in hand, we commissioned a K–12 grading service to assess ChatGPT’s writing. The human graders evaluated each essay using rubrics from the Tennessee Department of Education that were tailored to the grade level and writing task. The graders assessed the essays across four categories of criteria—focus and organization, idea development, language, and conventions—and produced a numerical grade.So what happened? And what does it mean for teaching and learning? You can—and should—read all the findings and conclusions for free at Education Next, along with some of the essays that ChatGPT produced and some of the human graders’ comments.

AI is almost certainly going to take up more and more discussion on this newsletter in the months to come. I recently joined Gary Kaplan of JFYNetworks, for example, on his podcast to talk more about AI. You can listen to the podcast here at “Artificial Intelligence: A Conversation with Michael B. Horn on ChatGPT.” Jeff Selingo and I will have an episode on Future U. about AI soon for you as well. And the Khan Academy recently introduced an integration with GPT-4 for tutoring. It’s not generally available yet, but you can check out the in-depth demo here. All to say: Things are moving incredibly fast. Stay tuned.

A Retrospective on Disrupting Class and Clay Christensen

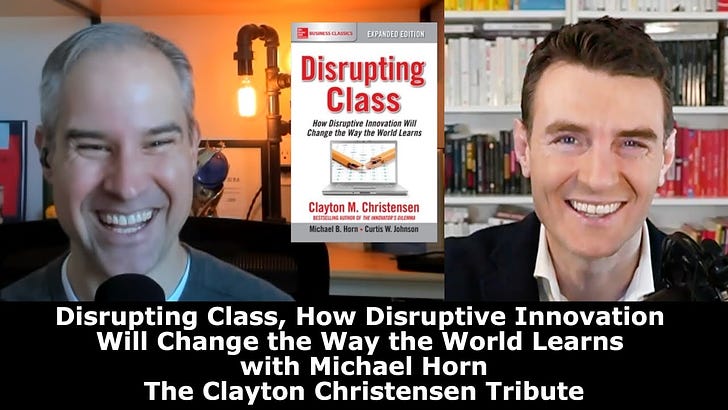

Aidan McCullen hosts a show called “The Innovation Show.” In recent weeks, he’s embarked on an ambitious series of shows in which he’s interviewed a wide range of Clay Christensen’s collaborators: Matt Christensen, Michael Raynor, Scott Anthony, Mark Johnson, Karen Dillon, Bob Moesta, and more. I joined Aidan to revisit our book Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns. You can check out the show here.

Over the last several years, Aidan’s become a remote friend (he’s based in Dublin) through the conversations we’ve had about innovation and education, as well as because of our shared passion (and sometimes borderline obsessions) around health, fitness, and wellness.

There’s also a real treat in the show: an up-front video of Clay talking about me and Disrupting Class back in 2008 or 2009. I won’t lie. Seeing Clay before he had had his first stroke made me tear up.

Aidan and I then dove into the why behind Disrupting Class, what the theories have to say, intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation and Jobs to Be Done theory, interdependence and modularity, and more. I ended with a few reflections of my own about Clayton Christensen. You can also watch the show on YouTube here:

From Reopen to Reinvent

Speaking of books, I’m continuing to speak about my recent book, From Reopen to Reinvent, in venues around the country. A talk at the Consortium for School Network’s (COSN) annual conference led to a couple articles in the media: here at EdTech magazine and here at Government Technology. I thought both did a good job of capturing some big themes from my keynote. And they both include some fun “action” photos as well.

Which leads to an ask! If you’ve read the book, could you please jump on to Amazon here and provide a review? More reviews help customers make better purchasing decisions—and, in this case, I hope will lead to more reinvention of K–12 schools that helps each and every student succeed. And thank you!

As readers of this newsletter know, I advance a major argument in the book that we ought to move away from seat time to mastery-based learning and a system in which we guarantee mastery for every child. In my keynotes, I’ve been speaking a lot about the lies we tell ourselves about our education system: how a system that embeds failure by design could possibly help all students recover the learning they missed during COVID, for example. Or how we continue to pay schools based on time rather than learning.

All of this background and more is why I was so gratified and excited to see Checker Finn’s recent piece for the Fordham Institute titled “Rewrite attendance laws to promote learning, not seat time.” I couldn’t agree more with the push (I’ve written about this a few times as well, such as here at “Fund Schools Based on Learning, Not Attendance—Especially on Yom Kippur”). If we’re serious about student learning, it’s well past time we started to make the shift.

Two New Podcasts

Finally, two new fascinating podcasts are now out.

First, as many of you know, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on affirmative action in higher education again in June. Most observers expect the court to end the use of race in admissions. But Jeff Selingo and I wanted to dig in more to what that might mean for higher education, so we brought on Jonathan Alger, the president of James Madison University, who played a key role as a lawyer in the University of Michigan’s Supreme Court cases 20 years earlier. Jon didn’t just offer a historical perspective on the show, he also explained how the Court’s decision will likely impact colleges and universities far beyond admissions. Check out the Future U. episode at “The Affirmative Action Conversation Colleges Should Be Having.”

Second, on Class Disrupted, Diane Tavenner brought up the topic of money. Yes, as Diane said on the podcast, “We talk about money all the time in schools and education, but what gets talked about is how there isn’t enough and how we need more. And if it goes deeper than that, it usually is about how we need more for teacher salaries because they don’t get paid enough and how we don’t have enough for art and music.”

But on this episode, Diane wanted to have another conversation—one that we almost never have in education. She wanted to start the conversation by asking what if we considered finances more explicitly as we served students—and looked to have the limits on money available be a means to drive innovation on behalf of students. She brought up a really fascinating example of how that doesn’t happen today in the realm of special education—and how limiting that is.

If we considered money in the course of our decisions in schools—and directed the scarce resources we have to those things that are actually working—what might that do to innovation on behalf of students? How might it change the culture and actions of schools? You can listen to our take here on The74, at “It’s Time We Talked Money.”

As always, thanks for reading, writing, and listening.

I've been playing around with the AI a bit, but it hasn't created a good enough output for me to use in professional writing without major edits. It also gives wrong answers. It apologizes when I correct it, and then gives a better answer. I read somewhere that a good analogy to this technology is "mansplaining", or confidentially telling me something that is not accurate, without qualification / hedging, and then pivoting when called out.

For all the speculation about ChatGPT’s potential to upend K–12 writing instruction, there has been little investigation into the underlying assumption that the AI chatbot can produce writing that makes the grade.Education decision makers are already moving to respond to this new technology. In January, the New York City Department of Education instituted a ban on ChatGPT by blocking access to it on all its devices and networks. Los Angeles, Oakland, Seattle, and Baltimore school districts have imposed similar prohibitions. As leaders in other districts, schools, and classrooms grapple with if, when, and how to make changes in response to this technology, they need a read on how well ChatGPT, in its present form, can deliver on the threat it is purported to pose.Daniel Curtisand I put OpenAI’s ChatGPT to the test by asking it to write essays in response to real school curriculum prompts. We then submitted those essays for evaluation. The results show that ChatGPT produces responses that meet or exceed standards across grade levels. This has big implications for schools, which should move with urgency to adjust their practices and learning models to keep pace with the shifting technological landscape.