Federal policy has immense power to influence incentives in higher ed. What can be done to better align them toward value and access?

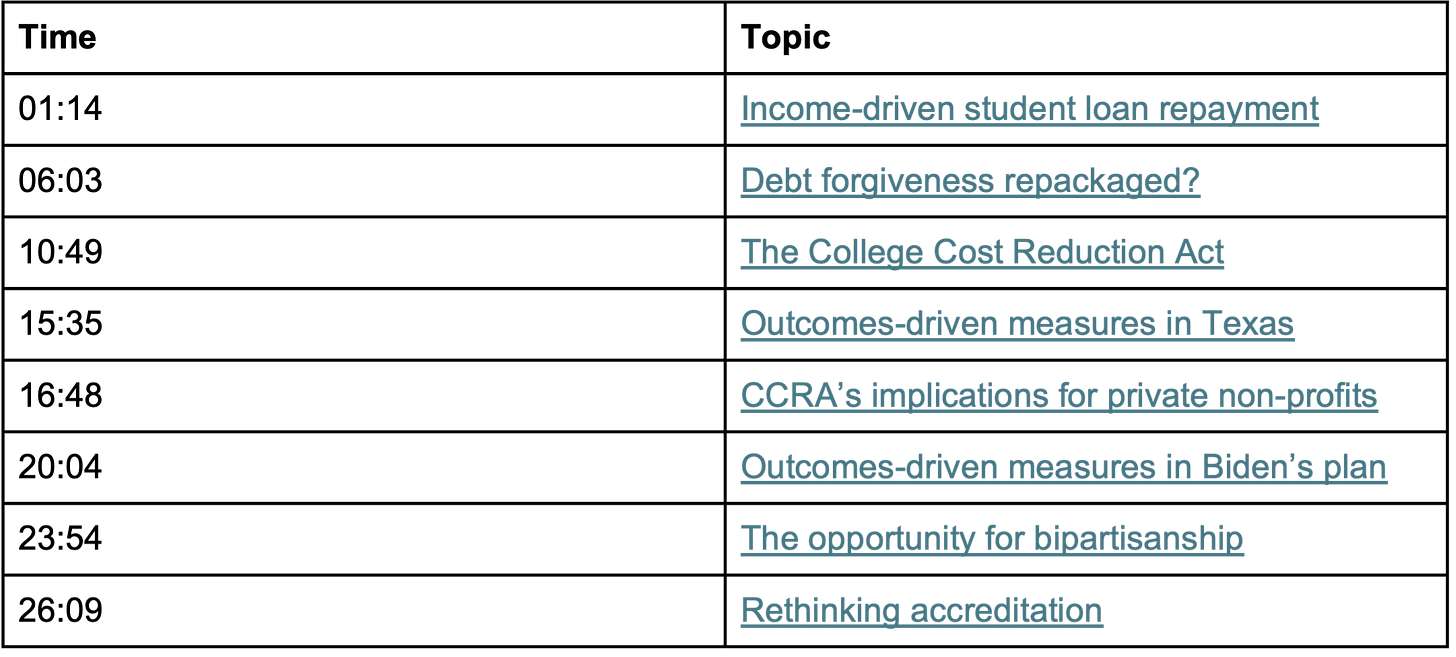

On the heels of my conversation with Phil Hill that posted last week, I sat down with , Senior Fellow at The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity (on Substack at ), to talk through the effect of enacted—as well as the potential of proposed—policies coming out of the executive and legislative branches. We tackled a series of topics: income-driven repayment, outcomes-driven measures, accreditation reforms, and the opportunity for bipartisanship.

Michael Horn:

Welcome to the Future of Education where we are dedicated to creating a world in which all individuals can build their passions, fulfill their potential, and live a life of purpose. To help us think through this is one of my favorite writers and analysts about higher education. A terrific thinker on smart policy to really put the power in individual's hands and focus on outcomes, reducing costs and the like for higher education. None other than Preston Cooper. He's a senior fellow at the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, focusing on the economics of higher education. Preston, first thank you for joining us. I've been absolutely loving your writing and I will confess the biggest challenge for me in prepping for this was deciding on where to spend our time because you've been writing about so many different interesting strands of how higher ed should and is changing at the moment.

Preston Cooper:

Well, thank you very much for having me, Michael, and thank you so much for the kind words about my work. I'm excited to dig into it with you.

Income-driven student loan repayment

Michael Horn:

Yeah, absolutely. Let's start off with the doozy. You're fresh off publishing this analysis where you found that a lot of the income driven repayment plans that are intended to help individuals, spare them in essence from defaulting on their student loans. That these actually backfire when the federal government is pushing individuals into these plans. I confess that was a total head-scratcher for me when I first read the headlines. I'd love you to break down what's happening and why and what's a better way forward if it's not these income driven repayment plans.

Preston Cooper:

It's a great question. I'll start by explaining what exactly income driven repayment is. If you have a federal student loan, you can enroll in these repayment plans, IDR plans, income driven repayment plans that allow you to tie your loan payments to your income. After a certain number of years of making payments on these IDR plans, you can get your remaining balance forgiven. It can be a fairly good deal for students in principle. Some students, if their incomes are low enough, are even able to qualify for a $0 monthly payment on the income driven repayment plans. About a third of borrowers during the time period that we're talking about here, which was 2018 - 2019, qualified for that $0 payment. The study that you referenced was done by a couple of economists who were affiliated with the US Department of Education and had access to a treasure trove of data that pros like us basically can't have access to.

We actually didn't know this before they took a look at the data. Basically what they did was they looked at those borrowers who qualified for $0 payments, so they didn't have to pay anything towards their loans because their incomes were low enough and they compared those borrowers to borrowers who were also on IDR, but whose incomes were slightly higher. They had to make very small but positive payments. They found that in the first year, those borrowers were enrolled in IDR. They had a big drop in delinquency rates as you would expect, if you have a $0 payment, you can't become delinquent on your loans. But after a year, something interesting happened, a lot of those borrowers became disengaged with the student loan system. They didn't enroll in auto debit, so their payments weren't automatically taken out of their accounts and often they forgot to recertify their participation in IDR.

If you want to be an IDR, you have to recertify every year, so the federal government knows what your income is and knows that you want to continue participating in the IDR plan. They found that borrowers who had that initial $0 monthly payment about 12 months after they first enrolled in IDR, had this huge spike in delinquency and they were more likely to become delinquent on their loans than borrowers who never had a $0 monthly payment. Which is a really wild finding that a $0 monthly payment is supposed to protect you from becoming delinquent on your loans. But it turns out that in the long run, borrowers who qualified for that $0 monthly payment were more likely to fall behind on their loans, more likely to face those adverse consequences such as a buildup of interest and potentially getting a hit on their credit scores that come with a student loan delinquency.

Michael Horn:

Wow. Totally unintuitive. What would a better path forward in your mind look like? How would you modify these income-driven repayment plans?

Preston Cooper:

I think that IDR is still an important safety net for borrowers. Sometimes life happens, things don't work out, and your student loan payment might be too high relative to your income. I think it's important to have a safety net there, but I think that this experiment with $0 monthly payments has proven to be a failure. What I would propose is even if borrowers are fairly low income, require a very small monthly payment, say just $25 a month, so that they keep getting into the habit of paying back their loans even if it's a very small amount. That way they don't become disengaged with the system. They remember they have this obligation that they need to continue meeting if they're going to have these loans. Also so that they don't necessarily have a big buildup of interest because they haven't been making payments on their loans.

Unfortunately, I think policy is kind of going in the wrong direction. The Biden administration about a year ago announced this big expansion of income driven repayment plans so that many more borrowers are going to qualify for a $0 monthly payment. Some of the preliminary data show that over half of borrowers who were enrolled in the Biden administration's new IDR plan are going to qualify for that $0 monthly payment. It's possible that that might increase delinquency rates in the long run because all those borrowers might simply become disengaged from the student loan system and not get into the habit of paying back their loans. I'm very concerned that this kind of well-intentioned expansion of IDR will end up backfiring on the borrowers it's supposed to benefit.

Debt forgiveness repackaged?

Michael Horn:

Absolutely fascinating. But it connects, I suppose to another part of the plot, if you will, which is of course the Biden administration was not stymied, say by the Supreme Court ruling saying that their student loan forgiveness plan was not legal. Instead, they've continued to try what you might call creative ways to cancel student debt. So, they might say, well, this is correct, but who cares because we don't think student debt should be a thing. Period. They've continued to try some different ways to get around this as I understand it, sending out some letters saying your student debt is canceled. Can you just bring us up to speed on where we are and what you expect to happen there?

Preston Cooper:

Absolutely. There's a number of different irons in the fire that the Biden administration has right now with respect to student loan forgiveness. Number one is the new income driven repayment plan that I mentioned a few minutes ago. Another kind of lower-profile effort to forgive student loans, which hasn't gotten quite as much media attention, is the second attempt. At one time, student loan forgiveness used a different legal authority than the Biden administration originally relied on for the loan forgiveness program that was struck down by the Supreme Court. So, they're relying on something called the Higher Education Act. They say, okay, well the Supreme Court said this other law that we relied on to forgive student debt, that's not going to fly. So, we're going to try again. We're going to use a different legal authority to use as a fig leaf for student debt cancellation.

They've been going through the process that they need to go through in order to try and propose something on student loan forgiveness here. It looks like we're getting close to a final plan that they may formally propose over the next few weeks or months. Essentially what they want to do here is they want to say, if you're a borrower who is experiencing hardship, we are going to give ourselves the power to forgive your student loans. But what does hardship mean? I'm not sure they entirely know, but that's not going to stop them from trying. Basically, they say, we're going to take all these factors about you into account. Whether you received a Pell Grant, whether you finished college, a whole bunch of different factors, 17 different factors, they have a whole list. They're going to put that into a black box model, which is not accessible to the public.

They're just going to pour all those factors into a model and out of that model is going to spit out an answer. Are you going to default on your loans in the next two years? If that answer is yes, then they're going to give themselves the power to forgive your loans. That's basically it. It's not necessarily a transparent process. They're going to put a bunch of factors into a model. It's not accessible to the public, and that model is going to say, you have the power to forgive student debt. I think this is problematic for a couple of reasons. Number one, I don't think they have any more legal authority here to forgive student debt than they did two years ago when they originally announced the loan forgiveness plan that the Supreme Court struck down. Number two, if this black box model is not accessible to the public and everybody who they say is going to default is going to get the loans forgiven, how are we ever actually going to test if that's an effective model? If you get your loans forgiven and you can't default on that, your loans. We can't really see if the model was effective at predicting your distress, your hardship. So, I am kind of very skeptical of this. I think that this is just an excuse to kind of forgive student loans on mass but give more of a scientific sheen to the way they're going about loan forgiveness than they may have approached it the first time.

Michael Horn:

Do you think we'll see another challenge in the courts as a result of all this, or is that path not as available this time around?

Preston Cooper:

I think it's fairly likely we'll see a court challenge to this as well. I mean, the same basic logic applies. The Biden administration has assumed itself a huge amount of power to forgive student debt for millions of borrowers with a taxpayer bill that could potentially run into the hundreds of billions. I think you have the same basic arguments that the state governments will probably sue over this as they did the last time. They'll say, this is clearly a major questions doctrine case. The Congress has to step in and say something. If you're dealing with dollar amounts that are just this big, the executive can't deal with those dollar amounts on his own. I suspect we will see another court challenge. It's probably going to take a while for that to make its way through the court. We may not have an answer right away, but I expect that we will eventually see the Supreme Court, or potentially a lower court, strike this down as clearly unconstitutional clearly goes against the spirit of the Supreme Court's ruling last June.

The College Cost Reduction Act

Michael Horn:

Gotcha. So, if that's on the executive side of the house, if you will, let's go to the other side of the house. The house itself and the Republicans there came out with this College Cost Reduction Act, which has a lot to like in my view, in the proposed legislation free up. You all had this exclusive look, I believe, at how the legislation would affect colleges and universities nationwide because it has this carrot-and-stick approach in it, which I'll let you describe. But I want to give this headline because it was so interesting to me. You found that public community colleges, particularly those with strong vocational programs, would receive nearly $2 billion per year in direct aid if this legislation passed. The bill is essentially rewarding these schools for their low prices, high socioeconomic diversity, as well as the fact that they largely don't rely, interestingly enough given the past conversation, on federal student loans. So, I found this striking because community colleges more generally, they're not places that get great outcomes in terms of completion rates or transfer and things of that nature, it seems very in line with the Biden administration's hope for community colleges getting money through other means. So, I'm just curious what is going on here in this policy?

Preston Cooper:

It's a great question. I'll start by kind of describing the carrot and stick approach in the legislation that you referred to. Let's start with the stick. Congressional Republicans are very concerned about the fact that a lot of students who use federal student loans to pay for their education don't earn enough to pay back those loans in full. We see a lot of people relying on IDR who are not paying back their loans, and who are getting the loans forgiven. We see a lot of people defaulting on their loans. So basically, what they want to do is make the colleges co-sign a portion of those loans. So, if the student either requires assistance to pay back their loans through an income driven repayment plan or doesn't pay back their loans at all, defaults all their loans. The legislation would require the colleges where the students went to compensate taxpayers for a portion of those losses that the taxpayers suffered because the loans went bad.

The goal here is to align incentives between the colleges and the students basically to say, if you're a college, you're charging way too much. Your students are taking on way too much debt relative to what they're earning after graduation, we're going to penalize you for that. So, you're either going to have to lower your prices to bring them in line with what you're graduates are earning, or you're going to have to figure out ways to make your education more valuable in the labor market so that your students earn more and that justifies the high prices that they're paying for your education. This raises a ton of money, obviously, because suddenly colleges rather than taxpayers are the ones who are suffering the losses on these student loans. And they plow a lot of that money into a new, what I call a performance grant program for colleges.

It's not just community college colleges that are eligible. All colleges who are participating in the federal loan program are eligible for these performance bonuses. These performance bonuses are given out based on a formula that takes into account how many low-income students you enroll, how good are your graduation rates, what are your students earning after graduation, and are you keeping your prices low. We kind of crunched the numbers on this, figuring out which colleges would benefit from these performance grants. It turns out community colleges do well. One big reason is that they have relatively low prices, and they have a lot of low-income students. Their outcomes are not necessarily great, the graduation rates leave something to be desired in the community college sector ditto with earnings. But I think it creates some incentives for community colleges to improve those outcomes because suddenly the community college can qualify for a potentially much bigger grant from the federal government if it invests in programs with a very high return on investments and if it invests in interventions to make sure more of those students get across the finish line.

So, we see, especially community colleges with a strong vocational and technical focus, community colleges, which you're focusing on the trades, getting graduates into very high-wage jobs, those colleges do well out of this performance bonus program. We see that if this legislation were enacted, a lot of community colleges, particularly if they have good outcomes, could do very well. And schools that are relying very heavily on the federal student loan program and don't have great outcomes, could take a major financial hit from that.

Outcomes-driven measures in Texas

Michael Horn:

This isn’t just theory, it occurs to me because you've seen this very thing play out in Texas, correct?

Preston Cooper:

That's right, yes. There's a college here in Texas called Texas State Technical College. And the state about 10 years ago kind of did something a little bit similar to what Republicans want to do at the national level. They said, for this technical college, we're going to overhaul the funding formula. So, you're no longer just getting an appropriation for how many butts you have in seats. Your funding from the state government is going to be based on what your graduates earn. We're basically going to give you a set percentage of your graduates' wages. This changed the incentives for the school so suddenly they can get more funding from the state government if they have better outcomes if their graduates go on to higher wage jobs. The community college essentially closed down some programs that were not paying off well for students and opened a bunch of new programs or expanded existing programs that did have a much better track record. It turns out the number of students they were serving went up, the average wages of graduates went up and their funding from the state government went up. So, it was a real winner for the college, but they had to be given the right incentives to make the changes they needed to make in order to serve students better.

CCRA’s implications for private non-profits

Michael Horn:

Incentives around outcomes matter. Fancy that. What was fascinating is that the story is quite different though for elite private universities. I want to quote what you wrote here because you said, that despite their vaunted reputations, many graduates of these schools do not earn enough to pay back the loans that they took out to afford the school's exorbitant tuition prices. This is especially true for top schools that have pricey master's degree programs of questionable economic value for the revenue. You estimated that elite private nonprofits would pay almost 2 billion per year. Sort of the opposite of the windfall, if you will, for the community colleges in penalties under the Republicans' plan. The biggest loser would be the University of Southern California USC, which would have to pay nearly $170 million annually if it continued with business as usual. So, help us unpack what's going on here. USC. Sure. They're everyone's poster child for bad behavior at the moment, but how about Harvard? Are they going to be paying money back to the federal government as well?

Preston Cooper:

A lot of schools that have pretty high prices and rely heavily on the federal student loan program could potentially be facing a really big bill. I want to emphasize, that it's the reliance on federal student loans that is the real killer for some of these schools. So USC to take that example, almost 1% of the new student loans issued in the United States every year just goes to USC. They're so reliant on the federal student loan program, and a big part of the reason for that is they offer master's degree programs. They charge over a hundred thousand dollars for say, a master's in social work. And the amounts that people are earning after graduation just simply are not enough to justify those debt burdens. So right now they can kind of get away with it largely because of safety net programs in the federal student loan program, like income driven repayment, which usually means students do not repay the loans they took out to fund their education at USC in full, but somebody's got to pay the bill for that.

And right now, it's taxpayers paying the bill. So the Republican proposal would say colleges are going to have to start footing a portion of that bill. So, USC, because it has all these programs where the debt is simply not justified by the earnings, could potentially pay a very large penalty under the Republican legislation. I believe the number is about 170 million per year. That's business as usual. But I think what a lot of the Republicans who authored this bill would say is that it's not necessarily about punishing USC, it's about changing the incentives to make sure USC does better by its students. We don't want USC to pay $170 million per year. What we want USC to do is to reduce its reliance on the federal student loan program, and bring down its prices so students don't have to pay quite as much to some of these programs that simply charge too much and don't have the earnings outcomes to justify it. Make USC a better school that does right by its students, and they won't have to pay that $170 million penalty. They continue with business as usual, though they're going to have to pay for it.

Outcomes-driven measures in Biden’s plan

Michael Horn:

Gotcha. I love it because that's a dynamic way to think about policy. It changes the marketplace incentives and actors rationally start to change what they do as a result. It circles back, I think, to the Biden administration because there are some ways to compare approaches here, right? USC, as I mentioned earlier, is sort of everyone's poster child, but especially theirs for everything that's gone wrong in higher ed in some respects. They talk about the bad contracts with online program management companies, and high-priced online master's degrees that you mentioned in fields like social work that don't get great earnings. On the other side, you've got the admission scandals at USC, you name it, they have it. The Biden administration has gone after some of this by revising the regs around third-party servicers. We might see them tackle the bundled services exemption with rev shares.

You've got the negotiated rulemaking that's going after online education more generally with state reciprocity and stuff like that. But they're also taking this approach that on the surface at least feels more outcomes oriented like the Republican plan to have institutions have skin in the game. And that's around the rewriting of the gainful employment regs. If I'm not mistaken, I think those regs have now been rewritten something like four times in the last 12 years, I think. You've done a lot of writing and thinking about gainful employment. How should we think about these contrasting approaches, gainful employment, looking at the loans people owe, and making judgments about programs versus risk sharing? Are there merits to both? Are there detriments to one or the other? What's your perspective on these approaches?

Preston Cooper:

It's a great question. So, to start with gainful employment, so what the Biden administration wants to do on gainful employment is they have a two-pronged test here. One, they look at each program that receives federal funding, how high is your student's debt burden relative to their earnings? And number two, are your students earning more than the typical high school graduates? And if you don't pass both of those tests, then you get kicked out of the federal student loan program. There is one massive, massive caveat to that though, which is that they only applied the gainful employment rule to for-profit colleges and career programs. So actually, places like USC, which as you said is kind of the poster child for malfeasance and higher education, they're going to be exempt from gainful employment. So that $115,000 master's degree in social work that leads to earnings of $40,000 or something like that, where students are never going to be able to pay back their loans without government assistance, that program would not be held accountable by gainful employment.

I think that's just a massive, massive blind spot in the rules that they were very obsessed with kind of targeting the for-profit college industry where there have been many legitimate problems there. I'm not defending them at all, but I think that means we can't simply ignore the problems that exist at nonprofits like USC because often they're not serving students well either, or they have a lot of these bad outcomes that the gainful employment rule completely ignores. That being said, I am kind of heartened at the focus on outcomes in that rule. I think I'm less of a fan of rules that are trying to go after third-party servicers or state authorization reciprocity agreements because I think if you can make an OPM work if you can make an online master of social work, if you can make that payoff for students, I don't particularly care that it's an online degree. I don't particularly care if you offered it with an OPM. What I care about is are your students’ getting earnings, and getting jobs that justify the debt they took on. No matter how you get to that point, as long as you can get to that point, I'm pretty agnostic as to the method you used to do it, but we have to make sure that the outcomes are there.

The opportunity for bipartisanship

Michael Horn:

Yeah, look, that mirrors my thinking as well. It seems like the focus should be on the outcomes, not micromanaging the inputs, which frankly is going to restrict innovation and favor incumbents in all sorts of weird ways from other fields. You certainly would conclude. I guess I'm curious about your perspective as a watcher of all this, does this create a bipartisan opportunity perhaps for some collaboration and compromise, at least given the recognition, hey, gainful employment, maybe it doesn't get all the actors we should risk sharing. Maybe we want to tweak that somehow. Is there some room between them for the two parties to come together and get some forward progress, maybe actually get legislation rather than just reg rewriting?

Preston Cooper:

It's a great question. It's something that I think about a lot. I think in principle, there's a lot of scope for potentially a grand bargain on this. I do think that both Democrats and Republicans recognize that there are big swaths of higher education that are federally funded and don't necessarily deliver on their promise. I think in principle, there's scope for an agreement there. I think it runs up against a number of practical hurdles starting with the fact that basically every member of Congress has a college in their district and some of those colleges don't do well. And some of those colleges might get penalized under any kind of reasonable risk-sharing or accountability framework. And so I think once you start getting to this practical consideration, some of the bipartisan consensus that makes sense in principle starts to fall apart. And that's why I think the carrot-and-stick approach of the Republican plan is pretty valuable because it's not necessarily just taking away from higher education, it's also benefiting a number of colleges that are doing right by their students. So members can go back to their districts and say, Hey, this community college is doing pretty well and they're actually going to get a bonus from this. And so I think that's to make this politically feasible, that's what's going to have to happen. We'll see whether the Republican plan can get any traction among Democrats right now. The Democrats have been pretty in lockstep opposed to it, but we'll see. It might be a good starting point for [a] potential grand bargain.

Rethinking accreditation

Michael Horn:

The future. Super interesting. So last piece of this, the College Cost Reduction Act also had this part that hasn't gotten a lot of attention around rethinking accreditation. And this might be a place for also bipartisan compromise because the way that the bill at least would propose is that you could have states creating what they call Q AEs, quality assurance entities, which is actually something borrowed a terminology borrowed from the Obama Administration's Department of Education in 2015. That would basically be new. I'd love your take on if you see this as an area for compromise, but also why introducing more accrediting agencies or defacto, I guess, accrediting agencies, why would this improve the state of affairs? Because it's not necessarily meaning that they wouldn't be membership organizations or that they would operate under different rules or anything like that. So what's the theory of action of introducing more accreditors or quality assurance entities?

Preston Cooper:

I think one massive issue that we face in higher education right now is there's a real dearth of competition, which means there's a real dearth of innovation. 95% of current traditional age college students attend a school that was started more than 40 years ago. There's simply not a lot of new entrants into higher education and not at the scale that can really provide competitive pressure to actually improve the state of affairs and higher education. And I think that's what those provisions of the college Cost Reduction Act are trying to get at. They recognize that a big problem here is the accreditors. So we have seven historically regional accreditors, which basically are the gatekeepers for new institutions seeking federal student aid and sometimes seeking just permission to operate. And those accreditors aren't necessarily friendly to new institutions. They're not necessarily friendly to innovation. Sometimes they'll just look at, if you want to start a new school, are you doing everything exactly the way other schools are doing it?

So that doesn't really add any value there. Leave much space for innovation. So the Republican proposal would allow some new institutions to kind of get around the established accreditation cartel. They'd still be held accountable, but they could be held accountable by the state governments, not necessarily by accreditation agencies, by allowing states to either create or designate these new quality assurance entities that would be able to approve new colleges or existing colleges for the purposes of access to Title IV federal financial aid. That's Pell Grants and student loans. And so this could inject some competition into the higher ed sector if suddenly new institutions with a new way of doing things with potentially a more cost effective model or potentially a model that might get better outcomes if those new institutions suddenly have an easier path into the market that could put some real competitive pressure on incumbent institutions to try and improve their outcomes, lower their prices do better by their students. Now naturally, there have to be some safeguards there, and I think the bill has some appropriate safeguards to make sure we're not just approving fly by night or scam institutions to get taxpayer dollars. But I think the goal there is to create more competitive pressure in the higher education market. And I think that's a very laudable and a very needed goal that they're trying to accomplish.

Michael Horn:

In other words, part of the argument is that the University of Austin, Texas is the Minerva. Universities reach universities. There's a handful of others, college Unbound, et cetera. Those are almost the anomalies that prove the rule that it's really hard to start up a new accredited higher ed institution. And we needed better gateway, in essence, to facilitate a lot more startups coming into the market.

Preston Cooper:

That's right. I have a magazine article about the University of Austin coming out soon, and when I was talking to them, one recurring theme was this is just a very drawn out process to start a new university. It's almost a year to get permission from the state government. It can be four to six years to get permission from the accreditor in order to operate. We've got to hire all these people who know how to navigate the bureaucracy, and I have no doubt that they're going to be able to do it. They've got $200 million behind them. They've got a bunch of big names, they've got a bunch of experts in navigating the accreditation bureaucracy. But if you're not the University of Austin and you don't have $200 million behind you, that's going to be a really steep hill for you to climb if you want to start a new university. And so they are the exception that proves the rule. They will probably be able to start a new college, and I wish them the best of luck. I think that their model's intriguing and it could be very successful, but we need more than just a handful of new colleges. We need large scale entry into the market to provide real competitive pressure to the established institutions, which up until now have been able to coast.

Michael Horn:

Super interesting. Preston, thanks for taking us through this rundown of all things intrigue and proposals and machinations behind the federal machine that creates a lot of the incentive structure for the very rational as a result behavior that we see in institutions in higher ed. Really appreciate you bringing the wisdom here on the future of education.

Preston Cooper:

Thanks for having me. It's a pleasure to have a conversation with you.

Share this post